by Michael Howell

How are we to understand the Wheatfield with Crows1 by Vincent Van Gogh? Or, for that matter, how are we to understand any painting?

As Heidegger has pointed out, “On the usual view the work arises out of and by means of the activity of the artist.”2 Rather than shun the ‘usual’ view in favor of a more ‘original’ approach, let us follow the path which this ‘naive’ or ‘natural’ reflection opens up and see for ourselves whether or not an inquiry into the “activity of the artist” does indeed lead to an understanding of the painting itself. Let us begin, then, by asking what it might mean to understand the Wheatfield with Crows as arising “out of and by means of” Vincent’s “activity”.

We might take this to mean that the meaning of the work is to be found in the ‘intentions’ of the man who ‘produced’ it. What could be more natural when confronted with the product of a man’s activity whose meaning escapes us, than to turn to that man and ask, “What did you mean by that?” This implies, however, in the ordinary sense, that the painter knows what he is doing, that the meaning of the painting is somehow ‘in his head’ before being put down upon the canvas. Vincent himself, however, would probably be the first to object to such an understanding of his work. In one sense, to be sure, we may say that Vincent went out that day with the intention of painting a wheatfield, just as at other times, he went out with the intention of painting olive trees or peasants. But we have completely overlooked the struggle involved in his painting if we think that he knew in advance explicitly and definitely, what such a ‘project’ might entail; as though, for instance, to paint a wheatfield was simply to apply the laws of perspective in order to reproduce a valid representation of what he saw.

No, Vincent approached the wheatfield less like the man who knows than like the man who has everything to learn. We must take him seriously when, albeit with respect to another one of his paintings he says, “I do not know myself how I paint it.”3

“My brush stroke has no system at all. I hit the canvas with irregular touches of the brush which I leave as they are. Patches of thickly laid on color, spots of canvas left uncovered, here and there portions left absolutely unfinished, repetitions, savageries. I am inclined to think that the result is so disquieting and irritating as to be a godsend to those people who have fixed, preconceived ideas about technique. “4

But what does this mean? That it is useless to try to understand such “savageries?” That the Wheatfield with Crows by Vincent is roughly equivalent to the formula of Dostoievsky’s Underground Man: 2+2=5? Is this painting something we will never understand precisely because it was meant to defy our understanding?

Anyone familiar with Vincent’s life would readily deny such intentions. Far from hiding in some basement and issuing whimsical canvases designed purposely to defy any understanding as proof of his radical individuality, Vincent, on the contrary and like any other painter worth his salt, painted with the hope of being understood. It pained him deeply, while working on the streets of Antwerp, for example, that people showed such a lack of understanding of his work, to the point of spitting tobacco juice upon his canvases.

Many people, faced with the apparently “irrational” aspects of Vincent’s activity, that is, that he did not know himself what he was doing, suggest that precisely because of this we should consider his paintings as arising, not so much from his ‘ideas’ about art, as from his ‘feelings;’ suggesting that perhaps what Vincent really wanted from people was not ‘understanding’ so much as ‘sympathy.’ Indeed, Vincent himself often seems to suggest as much. “As for me,” he once wrote his brother, “if I could find some people who I could talk to about art, who felt for it, and wanted to feel for it – I should gain an enormous advantage in my work – I should feel more myself, I should be more myself.”5

Certainly one cannot stand long before the Wheatfield with Crows without feeling a certain solitude and abandonment. Should we say then that the painting is a reproduction of Vincent’s ‘feelings?’ Surely we must agree with him that, “one who wants sentiment in his work must first of all feel it himself and live with his heart.”6

But, to repeat the question, does this mean that we can understand the work as a representation of Vincent’s feelings? If we are not to fall back on the notion that he painted a ‘thought’ or an ‘idea’ of his emotions that he had ‘in his head’ at the time, we seem constrained to admit a method of representation which would communicate, not sensible ‘ideas’ from one ‘understanding’ being to another, but brute ‘feelings’ from one ’emotional’ being to another. What we have in the painting then is not some ‘idea’ to be ‘re-cognized’ but a brute ‘feeling’ to be ‘felt again.’

But if we really did ‘feel again’ all Vincent’s loneliness and abandonment before the wheatfield, wouldn’t we also kill ourselves a few weeks after viewing it, just as Vincent did after painting it? Before running off half-cocked, however, let us quickly admit that no matter how we answer, or sidestep answering this question, our own suicide would not prove or disprove the theory of art as communication of emotions. If you or I, either one, were to kill ourselves two weeks after viewing the painting, it would be as difficult to relate that death to the viewing as it is to relate Vincent’s death directly to the painting of it.

In order not to get bogged down by the problems involved in verifying such a thesis, let me simply admit, along with others, that I do feel a certain loneliness and abandonment upon viewing this painting. But I must also admit that, given only this feeling, I am still hard put to say I have understood the painting. Strictly speaking, nothing has been understood. I have simply stood before the painting and ‘felt again’ all the loneliness and abandonment which Vincent felt before the wheatfield, provided, of course, that I have even felt that much.

Certainly by the time he paints the Wheatfield with Crows Vincent has admitted openly that his “reason has half-foundered.”7 “And it’s a fact,” he wrote his brother, “that since my disease, when I am in the fields I am overwhelmed by a feeling of loneliness to such a horrible extent that I shy away from going out.”8

But how then do we understand the Wheatfield with Crows? As one of the last pieces of work produced by a man whose career careens towards madness? Have we comprehended the meaning of the painting by understanding the tumultuous wheatfield as the ‘symbol’ of the violent emotional eruption of a man standing on the brink of madness, about to lose his grip on the world?

It has been argued that while Vincent’s early paintings show a certain logic in their stylistic development, the later paintings, especially the last ones, are best understood in relation to the above mentioned “disease.” But can we really say we have understood the painting if we turn to Vincent, as Cezanne reportedly once did, and simply say, “Sir, you paint like a madman!”9 No, we really haven’t understood anything yet, not Vincent, not Cezanne (who was also called a madman), and least of all, perhaps, have we understood the painting. If we really see nothing in this painting but the wild gesticulation of a drowning man, we would still have to understand how a man might drown on dry land, that is, we would still have to understand that “madness.” As the scandalous history of psychoanalysis shows, however, understanding madness is no easy matter.

Our own attempt to understand the painting has led me to acknowledge a feeling of loneliness and abandonment upon viewing it. In order to understand that ‘feeling,’ we have related it, as Vincent did, to his disease. But how are we to understand that disease?

Dr. Peyron, director of the hospital at St. Remy, and Dr. Felix Rey, at the hospital in Arles, both treated Vincent personally and both diagnosed his disease as epilepsy. A little medical research shows, however, that at the time epilepsy was a very broad term indeed, and it is generally agreed that, judging from the recorded symptoms, Vincent probably was not suffering from what we call epilepsy today, that is, a chronic disease of the nervous system causing convulsions.

Thus the very refinement of the term in modern medicine led Jaspers to conduct the first psychoanalysis of Vincent post mortem.10 While he hedges on the notion that Vincent’s last paintings should be seen not as ‘works of art’ so much as ‘symptoms’ of a disease, Jaspers strongly suggests that whatever artistic value the paintings might have is best determined through an understanding of the disease. The Wheatfield with Crows, then, perhaps more than any of his other painting, might be said to exhibit a form of schizophrenia which, if not exactly the cause of the painting, is at least the necessary condition for such a work.

Thus schizophrenia, defined by Jaspers as the “disintegration of the inhibitions of the normal adult,” when “viewed intellectually,” shows itself, on the positive side, as a liberating force, a “loosening up process” which “allowed for the onset of a period of productivity which was previously precluded.”

“Earlier there was a constructive scaffolding which informed all movement, which now progressively fades. The paintings have an inadequate effect, details appear by chance. Sometimes the lack of discipline virtually extends to smearing without a sense of form. This represents energy without content, or doubt and terror without expression. No longer are there any new ‘conceptual formulations.’,” writes Jaspers.11

As Minkowska points out though (in 1932), “the profound comprehension with which Jaspers, among others, speaks of van Gogh is by itself an argument against the diagnosis of schizophrenia.”12 But he doubts the diagnosis mainly because, as Jaspers also admits, he “finds no trace of such typical schizophrenic traits as dissociation, disintegration of the personality, or autism.”13

But let’s return to Minkowski’s analysis for moment. Rather than view Vincent’s madness as an “atypical form of schizophrenia,” Minkowska suggests that we understand it as a typical form of “psychic epilepsy” — as opposed to the more ‘physical’ kind, I suppose.

How then do we understand the Wheatfield with Crows?

“…there is a heavy and menacing sky which weighs down upon the earth as if wishing to crush it. The field of wheat moves tumultuously, as if wishing to escape the embrace of the hostile force watching over it. It makes a deperate effort to raise itself towards the sky, but the descending black crows accentuate further the imminence of the destruction, the fall, the annihilation. Everything is engulfed in the inevitable shock. All resistance is useless. Van Gogh himself put an end to his life and his work.”

“On this supreme note, the work of art and the psychosis become mingled; the latter, far from constituting exclusively a destructive factor heightens still more the opposition of the two movements (i.e. of elevation and fall) which, at all times, compete with one another in the creative spirit of van Gogh. Without a doubt, in Wheatfield with Crows, the artist has given striking symbolic expression to opposing inner forces. In our own more prosaic manner, we can say that these two movements, one of elevation and one of fall, form the structural base of epileptic manifestations, just as the two polarities form the base of the epileptoid constitution.“14“And one may note,” as Hedenberg does (in 1937), “that what in general is considered characteristic of schizophrenic art, if one may speak of this as art, is precisely its rigidity, angularity, and inertia…”15

Without pursuing the history of this post mortem psychoanalysis any further,16 let us take note of the problems involved in the psychologization of a work of art. Whether we take Vincent as an “atypical schizophrenic,” as Jaspers does, as a “psychic epileptic,” as Minkowska suggests, or simply as a “psychopath” in general, as G. Kraus does, because, “as a child he already was ‘strange,’ and his many abnormal characteristics (such as “hyper emotionality”) regularly brought him into conflicts with his surroundings and produced serious difficulties in his life,”17 still, we must be very careful about reducing, not only the meaning of the painting, but the meaning of the ‘illness’ to the “inner Tragedy of the artist.”18

Despite all the differing and even opposing diagnoses, surely we will all admit along with Kraus that, “there does exist general agreement that he was given to extremes and that his personality was characterized by many contradictions.”19 Without a doubt, there was something ‘wrong’ with Vincent. As his brother once confided to his sister, after living with Vincent in Paris for awhile, “It is as if he had two persons in him — one marvelously gifted, delicate and tender, the other egotistical and hard-hearted. They present themselves in turn, so that one hears him talk first in one way, then in the other, and this always with arguments which are now all for, now all against the same point. It is a pity that he is his own worst enemy, for he makes life hard not only for others but for himself.”20

Notwithstanding the kernel of truth contained in these analyses of Vincent’s ‘personal’ problems, we should remain cautious about the restrictions imposed in the psychologization of a work of art or an illness. In reducing the meaning of the painting to the “inner tragedy of the artist” we have overlooked a greal deal concerning the obvious socio-cultural value of the work. While Vincent himself sometimes spoke of his illness as being “more or less my own fault,”21 on the other hand, even more frequently, he was disposed to look for the meaning of his madeness ‘outside’ himself.

“Do not fear,” he once wrote his brother, “that I shall ever of my own will rush to dizzy heights. Unfortunately, we are subject to the circumstances and the maladies of our time.”22

And what were the “circumstances and the maladies of the time?” Well, the painters in particular, who had depended for generations and generations upon one patron or another to give support and direction to their work, were finding themselves (literally) out on the streets — alone, isolated, and abandoned; a postition shared (if we may use the term only half ironically) by many another “person out of work,”23 as Vincent came to call them.

Following the Dutch war for independence from Spain, “with,…the greater part of the nobility either taking sides with Spain or remaining neutral, the power finally passed into the hands of the bourgoisie. This meant that the traditional support-structure of art was destroyed, for unlike the aristocracy, middle class people were not used to acting as patrons — nor did they have the intention of doing so. In general painters could no longer work on commission. Now they had to work for a free market, first painting the pictures and afterward selling them.”24

At its most extreme this would take us to the notion that absinth poisoning or chrome-yellow poisoning are the cause of the 1’distortions11 in Vincent’s paintings.

Far from being set free from the domination of ‘the patron,’ being thrown into the free market actually meant something more like pleasing the new patron — but one who refuses to pay in advance and has very poor taste, to boot. The triumph of the free market was, as Zola put it, a “triomphe de mediocrite, de la nullite, de la absurdite.”

“What sometimes makes me sad is this:” wrote Vincent, “formerly when I started, I used to think ‘If only I made so or so much progress, I shall get a job somewhere, and I shall be on a straight road and find my way through life.’ But now something else occurs, and I fear, or rather expect, instead of a job, a kind of jail.”25

The ‘price’ for not pandering to decadent tastes was dear — and for many painters besides Vincent. But the painters were not the only ones feeling ‘alienated,’ that is, the old term for schizophrenic, or, as we have put it here, ‘lonely, isolated, and abandoned.’ Vincent himself ran into the same problem as a salesman in the art business even before he took up painting. As an art dealer Vincent’s ‘discriminating eye’ was already getting him into trouble. He often tried to talk his customers out of buying those “pretty pictures” which sold so well, and tried to interest them in something a little “cruder,” perhaps, but something with more feeling, more expression, more “something, I don’t know what,”26 as he was fond of quoting Rousseau. It was Vincent’s ‘educational pursuits’ in this regard, as much as it was his preoccupation with religion and his melancholy love life, which led to his dismissal from the company.

“Well, — it’s the old, old story — but of course, all those departments, officious as well as official, all that bookkeeping, it’s all nonsense, and that’s not the way to do business. Doing business is surely also action — a measure of personal insight and energy. That does not count now — that is handicapped.,” Vincent wrote his brother Theo.

“I think it very, very sad. In Uncle Vincent’s time they started with a few employees who were not treated nearly so arrogantly and like machines. Then there was real co-operation, then one could be in it with all one’s heart.”27

There was a de-personalization of the workplace (and not only of the workplace) going on throughout Europe in Vincent’s time, that threatened to cut the ‘heart’ out of labor. The family business which had prospered immediately following the revolution was now becoming a company business – ruled, not by the ‘old man,’ but by some ‘executive committee.’

“…but you know, I don’t agree with the general politics of the present day, because I consider them mean and carrying all the signs of decadence which will lead to a regular periwig and pigtail period! One might almost weep over what has been spoiled on every side…” he wrote his brother.28

Vincent’s brother Theo, too, was feeling anxious and threatened concerning his place in the family business. It was not the influence of a ‘crazy’ brother that got him into trouble with Goupil and Co. so much as it was his own ‘discriminating eye.’ The time and effort, not to mention the money, which Theo spent in support of Impressionists was certainly not appreciated by the company at the time. When Theo wrote Vincent saying that he might leave the company and try to make it on his own, Vincent could offer no reassurance.

“Well, look here, you are becoming more and more a ‘person out of work.’ You may go to England, you may go to America — it does not matter, you will be like an uprooted tree everywhere. Goupil and Co., if you come back to them, would give you the cold shoulder. For all that, one is uprooted, and the world reverses the facts and says you have uprooted yourself. The fact is — your place no longer knows you.”29

“Really, when I think of my own experience, when I think of how my working for some years at Goupil & Co. ended in my being drawn very strongly towards home, when I think how there followed for me an absolutley bewildering crisis, which soon left me entirely alone and how everything and everybody I had formerly relied upon changed completely and left me high and dry, when I think of these melancholy times, I am so afraid that the present will prove to be no firm ground under your feet.30

“Now you talk of the emptiness you feel everywhere, it is just the very thing I feel myself. Considering if you like the time in which we live as a great and true renaissance of art, the worm-eaten official tradition still alive, but really impotent and inactive, the new painters isolated, poor, treated like madmen, and because of this treatment actually becoming so, at least as far as their social life is concerned.31

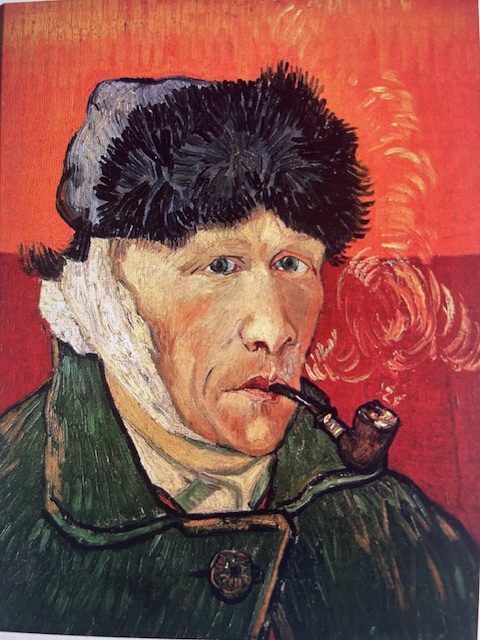

“I am thinking of accepting my role as a madman the way Degas acted the part of a notary. But there it is, I do not think that altogether I have the strength for such a part.”32

Vincent’s ‘madness,’ or better yet his ‘alienation,’ or, finally, his ‘loneliness and abandonment,’ was not simply his own. Like Nietzsche’s madman running through the streets proclaiming the death of God, Vincent’s madness, too, was in many respects simply a sign of the times.

As Nietzsche put it:

“The most important of recent events, that ‘God is dead,’ that the belief in the Christian God has become unworthy of belief — already begins to cast its first shadows over Europe. To the few at least whose eye, whose suspecting glance, is strong enough and subtle enough for this drama, some sun seems to have set, some old, profound confidence seems to have changed into doubt: our old world must seem to them daily more darksome, distrustful, strange and ‘old.’ …This lengthy, vast and uninterrupted process of crumbling, destruction, ruin and overthrow which is now imminent: who has realised it sufficiently today to have to stand up as the teacher and herald of such a tremendous logic of terror, as the prophet of a period of gloom and eclipse, the like of which has probably never taken place on earth before?”33

Vincent was not unaware of this “most important of recent events” as he himself put it, “…Victor Hugo says, God is an occulting lighthouse…and if this should be the case we are passing through the eclipse now.”34

But it was not only artists and philosophers who suffered under this Destiny. The “gloom” was widespread. By the turn of the last century, this “gloom” was to give rise to a new branch of medicine: psycho-analysis — following upon the heels of the hypnotists who had experienced a widespread, though fleeting, success in treating the new “malady.” The new disease was so widespread in England that Dr. Cheyne called it the “English Malady,” although Mesmer had no shortage of patients on the continent.35

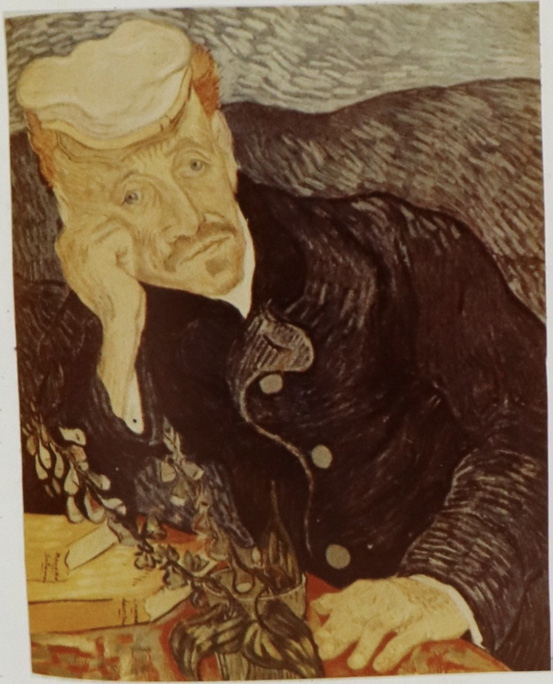

Finally, then, let us turn to Dr. Gachet, the last doctor to care for Vincent before his death. Though not a painter, his private collection of painting betrays his own ‘discriminating eye’ — a few Cezanne’s and a Pisarro, for example. It was a collection of contemporary works which Vincent, too, admired. He gave Vincent the “impression of being rather eccentric, but his experience as a doctor must keep him balanced enough to combat the nervous trouble from which he certainly seems to suffer at least as seriously as I do. However, the impression I got of him was not unfavorable; when he spoke of Belgium and the days of the old painters his grief hardened face grew smiling again. I think I shall end by being friends with him.”36

It would be a mistake, it seems, to understand the portrait which Vincent finally painted of that “grief hardened face” simply as the depiction of Vincent’s own emotions. The grief rendered visible in the portrait of Dr. Gachet should not be restricted to Vincent’s ‘inner’ feelings any more than to the doctor’s. It was a grief ‘out in the world’ that they both shared and the painting of it is indeed, to use Vincent’s own words, “the heart broken expression of the times.”37

“We moderns are just beginning to form the chain of a very powerful sentiment, link by link — we hardly know what we are doing…He who knows how to regard the history of man in its entirety as ‘his own history,’ feels in the immense generalization all the grief of the invalid who thinks of health, of the old man who thinks of the dream of his youth, of the lover who is robbed of his beloved, of the martyr whose ideal is destroyed, of the hero on the eve of the indecisive battle which has brought him wounds and the loss of a friend. But to bear this immense sum of grief of all kinds, to be able to bear it,…to have all this at last in one soul, and to comprise it in one feeling; — this would necessarily furnish a happiness which man has not hitherto known, — a God’s happiness,” wrote Nietzsche.38

Without approaching the enigma of how this “immense form of grief” might tend to a “God’s happiness,” let us return to the Wheatfield with Crows now that we have at least extended the “inner tragedy of the artist” to the vast proportions of the “outer tragedy of the times.”

Are we now to understand the “imminence of the destruction, the fall, the annihilation,” which Minkowska attributed to “opposing inner forces” as arising from opposing outer forces, instead?

Let us return to Minkowska’s description once again: “…there is a heavy and menacing sky which weighs down upon the earth as if wishing to crush it. The field of wheat moves tumultuously, as if wishing to escape the embrace of the hostile force watching over it.”39

Are we now to see in this struggle between a “heavy and menacing sky” and the “tumultuous” wheat field rising up against it, the symbol of the social conflict of the times? The tumultuous wheat field symbolizing, perhaps, all the downtrodden people of the earth, the laborers and the peasants, rising up against the heavenly domination of their bourgeois oppressors?

Such an interpretation is not so far fetched as it might seem at first,40 but in the end it is as inadequate and unsatisfying as the psychological account — and for many of the same reasons. Insofar as the “forces” at work in “producing” the painting are conceived of in causal terms, then, whether these causes are ‘internal’ or ‘external’ — in both cases we have misinterpreted the ‘nature’ of the artist’s ‘motivation.’

For whether we take the painting as a psychological statement of the impending breakdown of Vincent’s personality, or as a political (socio-cultural) statement of the impending breakdown of society — in both cases we are ignoring all but the ‘apocalyptic’ and ‘threatening’ aspects of the work.

The point here is not to deny this threatening aspect of the work, that is also, the way in which it violates all traditional standards of expression and defies the decadent tastes of the day. There is a threatening or menacing aspect to the painting; and if it has taken us this long to approach the more positive aspects of the painting, well, this only echoes, in a small way, the difficulties which many, in fact most, other people experienced in appreciating Vincent’s work. At first, like Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, all we hear or see is the glaring violation of our sensibilities.

Now, however, not only after his death, but after the birth and death of Fauvism, abstract expressionism, etc., it is easier to look back and see a certain ’logic’ at work, a certain consistency in stylistic development—even up to the end, even up to the Wheatfield with Crows. After all, here is another ’landscape.’ And what about the ’perspective’ brought to bear on that landscape? Does it not owe something to Corbet, to Durer? In fact, Vincent practiced many long hours using a perspective device which he built himself on the model of Durer’s—an empty frame with cords strung across it as an aid in analyzing the ’foreshortening’ of the lines of perspective.

We need only compare Wheatfield with Crows to Matisse’s The Snail, for example, to appreciate all the more how much of the realist tradition is retained in Vincent’s painting.

The Snail by Matisse

However ’inverted,’ however ’strange,’ however ’strained’ the perspective in this painting, that there is some sort of perspective being brought to bear is hard to deny. And besides, taken simply as one stylistic influence among others to which Vincent was exposed, we may add to this touch of ’realism,’ a touch of impressionism,41 even of symbolism,42 in fact, a host of other styles,43 and go a long way it seems in unfolding a lot of meaning couched in that ’mad’ and ’apocalyptic’ painting. After all is there not something of Monticelli in the thick impasto? Something of the Japanese in that concentrated quickness of expression that attempts to capture a whole stalk of wheat in two quick and clean strokes of the brush or a crow in flight in three? And one may even return to the halos in Byzantine art to find some equivalent to the pure, glowing radiance of being which Vincent tries to express through the use of color alone.

Without pretending to exhaust all the ’influences,’ or echoes of tradition, even foreign tradition, in the Wheatfield with Crows, we should ask ourselves first, if we are not now admitting precisely what we denied in the beginning of our reflections upon Vincent’s activity as an artist, that is, that he did not know himself what he was doing.

Philosophically speaking, we have arrived at a crucial juncture in our attempt to understand the Wheatfield with Crows. How could a man who ’knew’ so much about art claim to paint in ’ignorance?’ Certainly, in some sense, we must admit that Vincent ’knew’ his tradition very well. But once we admit so many little ‘reasons’ to account for various aspects of Vincent’s painting have we not then definitively denied that ‘ignorance’ and banished that ‘madness’ which has occupied us up to now—at least from our understanding of the painting?

If one were satisfied with understanding the outcome of a painter’s activity as a patchwork of borrowings this would seem to be the case. Here, however, we must insist otherwise.

Vincent doubtless had a lot to learn, not only from traditional European painters, but from the Japanese; as well as from his contemporaries. But that is just the point—Vincent always had a lot to learn from tradition, and if he never tired of looking again at his Japanese prints or the paintings in the museum, it’s because they always had something more to say to him. To forget how so many traditional paintings can hang continually on the walls of the museum like so many perpetual enigmas to a painter involved in learning the craft himself, is to shirk the philosophical struggle involved in understanding how so much knowledge of tradition always goes hand in hand with a certain kind of ignorance, when it comes to painting creatively.

Take the matter of perspective, for example. To think that Vincent had mastered the use of perspective as one encounters it in the tradition and that the differences one notes between the perspective of Wheatfield with Crows and anything preceding it may be accounted for by adding various other styles and techniques is absurd. But the notion that Vincent had mastered the use of traditional perspective at all finds little support in the strange, inverted perspective of the Wheatfield with Crows. In fact, one of the most common objections to Vincent’s work from the very beginning was that his perspective was “faulty.”

Van Gogh’s Chair 1888

If we do as one critic suggests, however, and build a perspective frame ourselves, and look at something like a chair, in close quarters, from slightly above, we see that at least some of what we took at first to be Vincent’s own personal distortions of perspective are actually distortions introduced by the perspective frame itself and that, at least with respect to the floor plane,44 Vincent accurately depicts what is seen once one has framed a certain area of space, isolated it from its surroundings, and fragmented this confined space with dissecting lines.

As Bremmer puts it in his discussion of the Potato Eaters (one of Vincent’s very first paintings):

“We are so bound by a specific tradition in art to certain ideal representations of space that these have been identified with reality itself. With an interior scene by Joseph Israels, to name but one example, there is enough room to move around in so that one gets a comfortable view of the inside of the house and consequently associates this with the idea of a realistic interior scene. Should it happen, which is seldom the case, that someone who loves this type of art should actually visit such a fisherman’s residence, then he is at once inclined to appreciate it through the eyes of the painter and not in terms of the actual setting…Small and confined as such residences are one can never gain a sufficient vantage point from which to view the whole setting; in truth, it is Israels who provides us an idealized representation of space, whereas it is Vincent, by contrast, who represents space as he sees it and as he is forced (in reality) to see it…People should realize from this how limited their ability is to observe reality objectively and how they are always inclined to abandon themselves to a predetermined manner of seeing.

“One may therefore describe the conception of the painting as realistic, since the artist commences with what he sees.”45

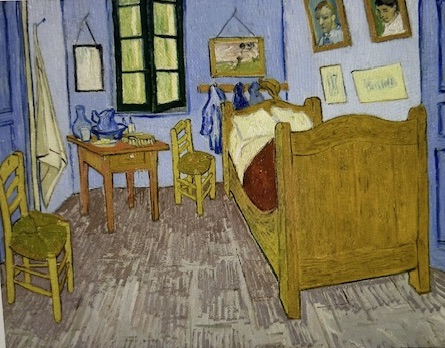

Or as the same critic put it in relation to the Bedroom at Arles:

Bedroom at Arles 1888

“Here again it is that well-known prejudice which threatens—namely convention, which has led to the depiction in art of things not as they are but as they are represented according to traditional formulas. In other words, paintings are made according to an ideal form of perspective, through which objects are depicted in terms of relationships determined by how people ’remember’ them to co-exist satisfactorily, but not by how people can ’observe’ such relationships from a single determined, physical position.” 46

As an art critic Bremmer provides us with some valuable insights into the “realistic aspects” of Vincent’s paintings, but as a philosopher or an artist, I feel he lets us down. Immediately after pointing out the “gains” Vincent had made towards a realistic depiction of what he sees, Bremmer then dismisses it as quite unimportant because “the significance of art is not determined by the degree of objective truth which is contained therein. The search for the truth does not belong to the domain of art but to that of philosophy.”47 What matters in art is the “psychological revelation” of the artist’s “feelings,” a revelation based not on ’observed’ reality but upon “everything the artist had preserved from his own earlier experience…collected together with the help of his memory.”48

“What then is the significance of such a painting (as the Bedroom at Arles)?” asks Bremmer “It is the room in which Vincent temporarily lay sick, ‘and to avenge myself I painted it. I went and painted my yellow bed as if with fresh butter’.”

“I do not quote this as an anecdote,” writes Bremmer, “because in terms of such considerations I remain unmoved, and one must avoid such narrative forms of appreciation. But that yellow of ’fresh butter’ is of importance here, since the quintessence of his feelings was therein contained. He wished to reproduce objects not as he perceived them, but as they gestated inside him into a positive image.”49

We have already grappled with some of the problems involved in the psychologization of a work of art in our discussion of the more ’negative’ aspects of the painting. It is interesting to see them crop up again, in slightly different terms, on the more ’positive’ side.

In no uncertain terms Bremmer has thrown the significance of art and painting into the realm of subjective imagination and simply divorced it from objective questions of truth and reality. Very few artists would accept lightly such a brash disregard for ’reality,’ especially with respect to the significance of their work. Vincent, for one, took both the ’realists’ and the question of ’reality’ more seriously, that is, more personally, than Bremmer is capable of acknowledging.

In dismissing the ’realistic aspects’ of Vincent’s work as relatively insignificant Bremmer has overlooked something about the ’depth’ of Vincent’s perspective. If Vincent never abandoned his fidelity to the real, to observation, to the patient study of appearances, to nature, and to the truth—this is not without significance! If he was full of deep feelings and welling over with past experiences as he painted Bedroom at Arles, nonetheless he was also standing there in that very same room, scrutinizing it even as he painted it, in an attempt to remain as faithful to what he saw immediately before him, as he was to all those memories and feelings.

”0f nature I retain a certain sequence and a certain correctness in placing the tones,” wrote Vincent, “I study nature, so as not to do foolish things, to remain reasonable; however, I don’t care so much whether my color is exactly the same, as long as it looks beautiful on my canvas, as beautiful as it looks in nature…. suppose I have to paint an autumn landscape, trees with yellow leaves. All right— when I conceive of it as a symphony of yellow, what does it matter if the fundamental color of yellow is the same or not? It matters very little.

“Much, everything depends upon my perception of the infinite shades of tone of one same family.

“Do you call this a dangerous inclination towards romanticism, an infidelity to ’realism,’ a ’peindre du chu,’ a caring more for the colorist’s palette than for nature? Well, que soit. Delacroix, Millett, Corot, Dupre, Daubigny, Breton, thirty names more, aren’t they the heart and soul of this century and aren’t they rooted in romanticism, though they surpassed romanticism?

“Romance and Romanticism are of our time, and painters must have imagination and sentiment. Fortunately realism and naturalism are not free of it.”50

The real philosophical task is to understand how this “realism” and how this “romanticism” might actually be two aspects of one and the same work. As Vincent, himself, put it:

“One starts with a hopeless struggle to follow nature, and everything goes wrong, one ends by calmly creating from one’s palette, and nature agrees with it, and follows. But these two opposites cannot be separated. The drudging, though it may seem futile, gives an intimacy with nature, a sounder knowledge of things…

“…though I believe the best pictures are more or less painted by heart, I can’t help adding that one can never study nature too much or too hard. The greatest most powerful imaginations have at the same time made things directly from nature that strike one dumb.”51

Vincent often ’explains’ his ability to unite realism and romanticism in a single painting as the combination of an objectively true drawing with the free, subjective use of color in the expression of ’feelings.’

In other words, like Bremner, Vincent understands his own work in terms of a dichotomy between the object and the subject of perception. The object is expressed as accurately as possible in the drawing through the use of perspective. The subject is also expressed as accurately as possible through the use of color, (i.e., their emotional value). The subjective is added to the objective as color is added to an initial line drawing; as though the arrival of a human being (painter or perceiver) necessarily colors a pre-existent state of affairs.

Thus, unlike Bremmer, Vincent insists that, “these two opposites cannot be separated.” Vincent, like Cezanne, shared the classical definition of art:

“L’art c’est l’homme ajute a la nature! I can still find no better definition of art than this: nature, reality, truth, but with a significance, a conception, a character which the artist brings out in it, and to which he gives expression, which he disentangles, sets free, and clears up.”52

If we pursue this classical definition in a straightforward fashion with respect to the Wheatfield with Crows, however, it soon becomes apparent that this simple ’explanation,’ upon close examination, yields; not a simple and clear understanding, so much as a wealth of hidden complexities.

Just the fact that by the time Vincent painted the Wheatfield with Crows he had already abandoned the practice of making a preliminary drawing does seem to raise a question concerning the classical understanding. If nothing else, it suggests that the combination of objective and subjective characteristics in this painting is not that of simple addition—if this implies that one precedes the other in a consecutive fashion. Somehow each is performed in a single act.

One thing seems certain concerning this point, and that is that we will never understand this combination of subject and object if to begin with we have already defined them as contradictory and then insist upon adhering to a logic of non-contradiction.

Meyer Shapiro, a contemporary art critic, makes a valiant attempt at overcoming this particular difficulty by employing a dialectical logic of “desire.” In the course of his attempt to express the ’dialectical’ nature of Vincent’s work, however, he offers us a remarkable and valuable insight into the nature of perspective, as he clearly perceives the subjective, expressive moment of Vincent’s work, not simply in the use of color, but in the use of perspective itself.

“Recall how Cezanne reduced the intensity of perspective, blunting the convergence of parallel lines in depth, setting solid objects back from the picture plane and bringing distant objects nearer, to create an effect of contemplativeness in which desire has been suspended. Van Gogh, by a contrary process, hastens the convergence, exaggerating the extremities in space. He thereby gives to the perspective its quality of compulsion and pathos, as if driven by anxiety to achieve contact with the world….as a beginner struggling with perspective…he already felt both the concreteness of this geometrical scheme of representation, and its subjective expressive moment. Linear perspective was in practice no impersonal set of rules, but something as real as the objects themselves, a quality of the landscape he was sighting. This paradoxical scheme at the same time deformed things and made them look more real; it fastened the artist’s eye more slavishly to appearances, but also brought him more actively into play in the world.”53

In rational terms, that is, compared to the traditional realist painters, both Cezanne and Van Gogh may seem to have faulty perspectives. Each seems to have bent the true laws of perspective to suit his own personal constitution. But if Cezanne and Van Gogh are exercising a certain liberty in their ’use’ of perspective, isn’t it akin to the liberty that the traditional realists also exercised when they ’used’ perspective to express their own love for, and training in mathematics?

Both Cezanne and Van Gogh noticed that when a line or the straight edge of a plane passes behind some object in our visual field, it emerges, not where one might ’think’ it would or should, but slightly out of line. Now if one is attempting to draw the edge of a table that passes behind someone’s arm, as in Vincent’s portrait of Dr. Gachet, on what grounds does one ignore what one sees with one’s own two eyes and impose some traditional formula for a mathematically straight line? And if one does decide to follow one’s eyes rather than use a ruler when drawing that line, does this make one’s drawing less true? Certainly it may make it mathematically incorrect—but untrue? As incorrect as the line may be, it is still true to what one sees.

Even to say that Vincent “hastens” the convergence of his perspective lines may be a misunderstanding. Perhaps the lines of Vincent s perspective converge at just the right point to convey not only the visual givens but also the way in which Vincent, himself, clung to the visual evidence, that is, not without passion. To say that the lines converge ’prematurely’ is to judge them according to a ’rule’ which does not apply to the visual ’givens.’ And if Cezanne’s perspective bespeaks a more ’’contemplative gaze,” isn’t that also the truth. Cezanne was known to require up to 500 sittings for a portrait— always in the same pose. Vincent, on the other hand, had trouble getting models to sit for him. If someone did sit for him, more than likely the portrait would be finished by the end of the day. For the most part, though, Vincent learned while drawing people in action.

But if Vincent and Cezanne both balked at the ’constructive’ aspects of traditional realism and appealed instead to the ’visual givens’ it would be a mistake to call their realism ’empirical.’ Holding to the visual givens does not mean reducing one’s work to some kind of ’photographic’ or ’imitative’ realism. As Vincent put it:

“If one photographs a digger, he would certainly not be digging then….I adore the figures of Michael Angelo though the legs are undoubtedly too long, the hips and backsides too large….my great longing is to make those very incorrectnesses, these deviations, remodelings, changes in reality, so that they become, yes, lies if you like—but truer than the literal truth.”54

Vincent’s inclusion of himself in his perspective is not, as Bremmer described it, simply forcing the eye of the rationalist into a “single, determined, physical position,” as though putting a camera up against the fourth wall of Vincent’s bedroom might yield the same picture;’ without, of course, the ’psychological effects’ of Vincent s use of color. As Shapiro suggests, it takes an eye with feeling to account for just that distortion of perspective which tends to draw the viewer into that world where things are not so much the object of contemplation, or of calculation, as of “desire.”

Provided one accepts Shapiro’s own remodelling of the truth, that is, not as objective or subjective but as the dialectical interplay of “desire” between the two, then we have come a long way in seeing the truth, it seems, in Vincent’s use of perspective. But what about the painting as a whole? If you remember, Vincent himself, explained the truth of his painting as the combination of a drawing, true to what he saw, and the use of color, true to what he felt. Shapiro has shown us how the union of these two ’truths’ can be seen in the drawing alone. What about the use of color, then?

Once again, even for the skilled dialectician, a contradiction emerges which cannot be integrated into his ’logic.’ It’s as though Vincent’s ’feelings’ refuse to play the game of “desire” in reality. The whole question of madness comes back to haunt us. “Contrary impulses away from reality assert themselves in a wild throb of feeling.55 Unable to contain these ’feelings’ in reality he turns to the use of “symbolic” coloring, and “resolves to paint less accurately, to forget perspective, and to apply color in a more emphatic, emotional way.”56

But if we examine closely Shapiro’s own remarks concerning the way in which this “religious sentiment,” this “flight from reality” is actually expressed in Vincent’s paintings, we begin to wonder whether there is not something a little one-sided about Shapiro’s dialectics, and something too limited about his own notion of ’reality.’

If in Vincent’s early work the convergence of his perspective ’hastens’ our eye towards its ’goal,

“In his later work, this flight to a goal is rarely unobstructed or fulfilled; there are most often counter—goals, diversions. In a drawing of a plowed field, the furrows carry us to a distant clump of bushes, shapeless and disturbed; on the right is the vast sun with its concentric radiant lines. Here there are two competing centers or central forms; one, subjective; with the vanishing point, the projection of the artist not only as a focusing eye, but also as a creature of longing and passion within this world, the other, more external, object-like, off to the side, but no less charged with fulfillment; yet they do not and cannot coincide. Each has it’s characteristic mobility, the one self-contained, but expansive, overflowing, radiating its inexhaustible qualities, the other pointed intently at an unavaiable goal.,” writes Shapiro.

“In the Wheatfield with Crows these centers have fallen apart. The converging lines have become diverging paths which make impossible the focused movement towards the horizon, and the great shining sun has broken up into a dark scattered mass without a center, the black crows which advance from the horizon toward the foreground reversing in their approach the spectators normal passage to the distance, he is, so to speak, their focus, their vanishing point. In their zigzag lines they approximate with increasing evidence the unstable wavy form of the three roads; uniting in the transverse movement the contrary directions of the human paths and the symbols of death.

“If the birds become larger as they come near, the triangular fields, without distortion of perspective, rapidly enlarge as they recede. Thus the crows are beheld in a true visual perspective which coincides with their emotional enlargement as approaching objects of anxiety; and as a moving series they embody the perspective of time, the growing imminence of the next moment. But the stable, familiar earth seems to resist perspective control. The artist’s will is confused, the world moves toward him, he cannot move towards the world. It is as if he felt himself completely blocked, but also saw an ominous fate approaching. The painter/spectator has become the object, terrified and divided, of the oncoming crows whose zigzag form, we have seen, recurs in the diverging lines of the three paths.”57

Like the zigzag route of the crows, like the wavy lines of the roads, Vincent, (at least as Shapiro sees him) was wavering in “pathetic disarray” before a world that had turned upon him, reversed the lines of his perspective, and made of him a “terrified and divided” object. It is in the face of this ’madness,’ as Shapiro sees it, that Vincent resorts to mathematical calculations.

He writes, “Just as a man in neurotic distress counts and enumerates to hold on to things securely and fight compulsion. Van Gogh in his extremity of anguish discovers an arithmetical order of colors and shapes to resist decomposition.

“The largest and most stable area is the most distant—the rectangular dark blue sky that reaches across the entire canvas. Blue occurs only here and in fullest saturation. Next in quantity is the yellow of the Wheatfield, which is formed by two inverted triangles. Then a deep purplish red of the paths—three times. The green of the grass on these roads—four times….Finally, in an innumerable series, the black of the oncoming crows. The colors of the picture in their frequency have been matched inversely to the largeness and stability of the areas. The artist seems to count: one is unity, breadth, the ultimate resolution, the pure sky; two is the yellow of the divided, unstable twin masses of growing corn; three is the red of the diverging roads which lead nowhere; four is… green;…n in the series is the endless procession of crows….”58

The unity of the painting then is ‘abstract’ in character—a mathematical-geometrical order imposed upon the ‘visual givens’ because, in the last resort, it is the only way left to restore order when reality itself is “disintegrating” before one’s very eyes.

What we have in the end, then, is a contradiction impervious to the logic of Shapiro’s dialectic. But if this is so, I would suggest it has as much to do with his dialectic as it does with “disintegrating reality.” I have already suggested a word of caution concerning the ‘one-sided’ nature of his dialectic, and now I might add that in terms of the Wheatfield with Crows, I very much doubt that the “unifying elements” in the painting are very well conceived in terms of mathematics and geometry alone.

The ‘problem’ that Shapiro’s dialectic leaves us with is understanding how it is that despite the disintegration and breakdown of the real (which he has defined in terms of perspective), this abstract mathematical and geometrical scheme, originating in a flight from the real, may nonetheless hold things together in a painting of the real. What is the connection between this painterly painter who manipulates and arranges colored shapes upon a canvas, and that painter who, nonetheless, looks up from his work in order to see what it is that he’s painting? And if the unity of the painting is achieved principally through a flight from the real doesn’t this mean that it is not unified in reality?

Though Shapiro claims to understand how the painting may be both an approach to the real and a flight from the real, it is not through his dialectical logic, but simply by denying the ’reality’ of a certain contradiction (between the ’real’ and the ’unreal’) while at the same time insisting upon its ’reality.’

Perhaps we can make sense of what might seem like philosophical gibberish concerning ’reality’ and ’unreality’ by returning to Shapiro’s explanation of how Vincent’s ’’unreal feelings,” his unruly “religious sentiment” which has no “real” object corresponding to it, nonetheless makes a place for itself in the painting.

This is important, and it bears a remarkable resemblance to the enigma which we put off approaching in our discussion of the more ’negative’ aspects of the painting. It is worth quoting Shapiro at length.

“In the letter to which I have referred, Vincent wrote to his brother: ’Returning there, I set to work. The brush almost fell from my hands. I knew well what I wanted and I was able to paint three large canvases.

“They are immense stretches of wheat under a troubled sky, and I had no difficulty in trying to express sadness and extreme solitude.’

“But then he goes on to say what will appear most surprising: ’You will see it soon, I hope… these canvases will tell you what I cannot say in words, what I find healthful and strengthening in the country.’

“How is it possible that an immense scene of trouble, sadness and extreme solitude should appear to him finally as ’healthful and strengthening’?

“It is as if he hardly knew what he was doing. Between his different sensations and feelings before the same object there is an extreme span or contradiction. .. .when he looks at his finished work, he more than once seems to see it in a contradictory way or to interpret the general effect of a scene with an impassioned arbitrariness that confounds us. In another letter he describes a painted version of the plowed wheatfield with sun and converging lines also depicted in the drawing mentioned above as expressing ‘calmness, a great peace.’ Yet by his own account it is formed of a ’rushing series of lines, furrows rising high on the canvas;’ it exhibits also competing centers which create an enormous tension for the eye…. Similarly, Van Gogh speaks of a painting of his bedroom in Arles as an expression of ’absolute repose’— yet it is anything but that, with its rapid convergences and dizzying angularities….It is passionate vehement painting, perhaps restful only relative to a previous state of deeper excitement.

“In this contradiction between the painting and the emotional effect of the scene or object upon Van Gogh as a spectator, there are two different phenomena. One is the compulsive intensification of the colors and lines of whatever he represents; the elements that in nature appear to him calm, restful, ordered, become in the course of painting unstable and charged with a tempestuous excitement. On the other hand, all this violence of feeling does not seem to exist for him in the finished work, even when he has acknowledged it in the landscape.

’’The letters show that the paradoxical account of Crows in the Wheatfield is no accidental lapse or confusion. They reveal, in fact, a recurrent pattern of response. When Van Gogh paints something exciting or melancholy, a picture of high emotion, he feels relieved. He experiences in the end peace, calmness, health. The painting is a genuine catharsis.”59

Unable to extend his dialectical analysis of Vincent’s perspective to his use of color, Shapiro resorts to Aristotle’s classical cathartic explanation of Tragedy which has no sound philosophical base in his own dialectic.60 But even apart from the problem of color, there is still something very disturbing about Shapiro’s account of Vincent’s loss of perspective.

Like Bremmer before him, Shapiro is overlooking something about the depth of Vincent’s perspective. In a nutshell, what strikes Shapiro as most ’disturbing’ appears reasonable enough to me, where he sees ’disintegration,’ I simply see a deepening.

For example, one might describe the duplication of the focal point, which is the first disturbing element in Shapiro’s account of the disintegration process, not as an objective representation of a disrupted dialectic of desire, but simply as the natural consequence of Vincent’s exploration of what we might call, following the phenomenologists, “lived perspective.” After all, wasn’t it the ’stage’ perspective of the Renaissance that tended to freeze or fixate our focus upon a single object which usually occupied center stage? Far from rivaling true perspective and threatening to disintegrate it, isn’t Vincent, through the duplication of the focal point, once again, simply being true to what he sees—the way in which things rival for our gaze as our un-fixed eye explores the ’scene?’

And if there is no single or even double focal point in the Wheatfield with Crows does this make it less true to what we see when, freeing our gaze from its mooring in things we scan the far horizon— not focusing upon any point as though we “desired” to go there—but simply to take in the “wide aspects of the countryside?”61

Even that reversal of perspective that Shapiro finds so “terrifying,” and attributes to an “hysterical desire to be swallowed up,”62 isn’t it, too, simply a natural consequence of Vincent’s exploration of ’lived perspective’? If a painter takes the ’notion’ of perspective and rigorously pursues it in terms of what he sees ‘out there’, in ‘reality,’ inevitably the roles between him and the visible are reversed.

’’That is why so many painters have said that things look at them. As Andre Marchand says, after Klee: ’In a forest I have felt many times over that it was not I who looked at the forest. Some days I felt that the trees were looking at me, were speaking to me…I was there listening…I think that the painter must be penetrated by the universe and not want to penetrate it…I await to be inwardly submerged, buried. Perhaps I paint to break out.’”, notes French philosopher Maurice Marleau-Ponty.63

It is concerning the nature of this reversal that Merleau-Ponty holds up a mirror and asks us to see in it the “emblem of the painter’s way.”

“In paintings themselves we could seek a figured philosophy of vision—it’s iconography, perhaps. It is no accident, for example, that frequently in Dutch paintings (as in many others) an empty interior is ’digested’ by the ’round eye’ of the mirror. This pre-human way of seeing things is the emblem of the painter’s way. More completely than lights, shadows, and reflections, the mirror image anticipates within things the labor of vision. Like all other technical objects, such as signs and tools, the mirror image arises upon the open circuit (that goes) from seeing body to visible body. Every technique is a ’technique of the body.’ A technique outlines and amplifies the metaphysical structure of our flesh. The mirror appears because I am seeing-visible (voyant-visible), because there is reflexivity of the sensible; the mirror translates and reproduces that reflexivity. My outside completes itself in and through the mirror. Everything I have that is most secret goes into the visage, this face, this flat and closed entity about which my reflection in the water has already made me puzzle. Schilder observes that, smoking a pipe before a mirror, I feel the sleek, burning surface of the wood not only where my fingers are but also in those ghostlike fingers, those merely visible fingers inside the mirror. The mirror’s ghost lies outside my body, and by the same token my own body’s invisibility’ can invest the other bodies I see.

“Here my body can assume segments derived from the body of another, just as my substance passes into them, man is mirror for man. The mirror itself is the instrument of a universal magic that changes things into a spectacle, spectacles into things, myself into another, another into myself. Artists have often mused upon mirrors because beneath this ’mechanical trick,’ they recognized, just as they did in the case of the trick of perspective, the metamorphosis of seeing and visible which defines both our flesh and the painter’s vocation. This explains why they have so often liked to draw themselves in the act of painting (they still do— witness Matisse’s drawing), adding to what they saw then, what things saw of them. It is as if they were claiming that there is a total or absolute vision, outside of which there is nothing and which closes in over them. How can we name, where in the realm of the understanding can we place these occult operations, together with the potions and idols they concoct? What can we call them? Consider, as Sartre did the smile of a long-dead king which continued to produce and reproduce itself on the surface of the canvas. It is too little to say that it is there as an image or essence; it is there as itself, as that which was always most alive about it, as soon as I look at the painting. The ’instant of the world’ that Czanne wanted to paint, an instant long since passed away, is still thrown at us by his paintings. His Mount St. Victoire is made and remade from one end of the world to the other in a way that is different from, but no less energetic than, that of the hard rock above Aix. Essence and existence, imaginary and real, visible and invisible—a painting mixes up all our categories in laying out its oneiric universe of carnal essences, of effective likenesses, of mute meanings.”64

The reversal of perspective in the Wheatfield with Crows does not simply make of Vincent, (or the viewer) a “terrified and divided object,” unless we also admit that a “terrified and divided object” can still paint or see. Like the mirror, that flat surface that we nonetheless seem to see ‘into’ in such depth, we are also ‘taken in’ by Vincent s painting. But just to the extent that we are truly taken in by this mirror trick of perspective, we simultaneously find ourselves ‘turned out’ in a most remarkable fashion, so that in some profoundly ambiguous sense, we might say that we are taken ’out into’ that Wheatfield near Aix, near the turn of the last century. Or if you will, a vision of that Wheatfield near Aix at the turn of the century suddenly appears before us here and now. But, to emphasize the point, it is too little to call this vision of the wheatfield an image or an essence, “it is there as itself, as that which was always most alive about it, as soon as I look at the painting.”

But if it really is too little to call it an image or an essence, by the same token, it is perhaps too much to call it the thing itself. A painting, after all, is really neither a mirror nor a window, but something else altogether, it seems. Something almost transparent, it’s true, like a window gaping open upon a world that literally surrounds it; something shiny and reflective as well; but also something solid, opaque, weighty and thick, something we could carry around like a sack of potatoes, after all, something we could burn or destroy. How are we to understand this strange talisman of the visible world which somehow has either the power to transport us into a world gone by, or else the power to conjure up a vision of a world gone by which comes to haunt us more substantially than any ghost could?

If the meaning of Vincent’s painting keeps eluding us in some way, if all the ’explanations’ of his work to date seem somehow inadequate and wanting (even his own ’explanations’), perhaps it’s wise for a philosopher to think twice before thinking he can ’explain’ it any better; especially if the philosopher’s ’explanation’ is based upon a reasoning which always resolves itself into contradictions and antinomies. Even a dialectical ’explanation’ that claims to think through contradictions has not exhausted the meaning of this painting.

The meaning of a painting, the meaning of the artist’s ’activity,’ will never be completely ’explained’ precisely because when the painter picks up his brush, or when something catches our eye on the museum wall, we are at the beck and call of a life which washes over all our nice categories and refuses to be exhausted by any artificial contra-distinctions.

“0 sancta simplicitas! In what strange simplification and falsification man lives! One can never cease wondering once one has acquired eyes for this marvel!…Even if language, here as elsewhere, will not get over its awkwardness and will continue to talk of opposites where there are only degrees and many subtleties of gradation;…— here and there we understand it and laugh at the way in which precisely science at its best seeks most to keep us in this simplified, thoroughly artificial, suitably constructed and falsified world!” wrote Nietzsche.65

One should not forget, though, how much Nietzsche loved to laugh at himself as well, and, as we shall see later, he too engages in the ’science of simplification.’ Who doesn’t?

It is not a question of abandoning all ’explanations’ so much as it means examining all those past ‘explanations’ in the light of that which they claim to explain, just as we have examined various explanations’ of the Wheatfield with Crows by continually returning to the painting and finding them wanting in so many respects; that is, in much the same fashion that Vincent examined the laws of perspective given him by others, (either in books or in paintings) by holding them up in the space and depth of “life as he lived it;” thus measuring them in terms of that ’space’ and that ’depth’ which they were meant to express.

It was a problem, as Vincent put it, not of painting the green at the top of that tree “against” the blue background of the sky, but of painting the green at the top of that tree “in” the blue of that sky. He mentions Gericault and how his “figures have backs even when one sees them from the front, there is airiness around the figures— . ..they emerge from the paint.”66

But besides this ‘airiness,’ which extends not only around the figures we see, but around the painter (or perceiver) as well, who also ‘figures’ in the scene; there is also that ground upon which the figure stands, and it too extends beneath the painter and behind him. In fact, the painter is, like the rest of us it seems, not only surrounded, but penetrated by the very elements involved in his painting and which he seeks to express.

Rather than rely simply on the “trick” of perspective to convey the ‘illusion’ of depth on a two-dimensional surface, Vincent, like Cezanne, was on the verge of translating the ’problem of depth’ into other terms. He was beginning to explore the way color alone might do the “trick” just as well67— an experiment which many moderns take for granted in much the same way that many of Vincent’s contemporaries took the efficacy of perspective for granted, that is, simply a matter of fact, while for others these mirror tricks of color and perspective remain nothing but problems to be solved.

Vincent, however, was one of those lucky ones who, through hard work, was able to get beyond the work, and who, in raising the question, found the things of the world approaching and offering their own solutions.

“Now I understand, more than I did six months ago, why Mauve said, ’Don’t talk to me about Dupre, but talk about the bank of that ditch, or something like it.’ It sounds rather crude, but it is perfectly true. The feeling for the things themselves, for reality, is more important than the feeling for pictures—at least it is more fertile and enlivening.”68

A generation before Husserl would raise the rallying cry amongst philosophers, the painters were already turning to “the things themselves.” Vincent, like Cezanne, was attempting to bring all that culture, history, and personality—all that ’humanness,’ all that labor and study, back into contact with the ground and atmosphere that gave birth to it in the first place.

This is less the abandonment of culture, history, and personality than it is their resuscitation in the open air, their revitalization through enrootment in the earth. Cut off from things, cut off from the open air and the earth, culture withers, and in such a wasteland the “savageries” of a true artist, must seem, indeed, something of a “godsend.”

Nietzsche called the ’founding’ of culture and society a returning to the earth, to nature, and to the body; and his own description of the artist’s relation to the things themselves is especially interesting insofar as it is the voice of one of Vincent’s contemporaries.

“Has anyone a clear idea of what poets of strong ages have called inspiration? If not, I will describe it—If one had the slightest residue of superstition left in one’s system, one could hardly reject altogether the idea that one is merely incarnation, merely mouthpiece, merely a medium of overpowering forces. The concept of revelation—in the sense that suddenly, with indescribable certainty and subtlety, something becomes visible, audible, something that shakes one to the last depths and throws one down—that merely describes the facts. One hears, one does not seek, one accepts, one does not ask who gives; like lightening, a thought flashes up, with necessity, without hesitation regarding its form.—I never had any choice.

“A rapture whose tremendous tension occasionally discharges itself in a flood of tears—now the pace quickens involuntarily, now it becomes slow; one is altogether beside oneself, with the distinct consciousness of subtle shudders and of one’s skin creeping down to one’s toes; a depth of happiness in which even what is most painful and gloomy does not seem something opposite but rather conditioned, provoked, a necessary color in such a super abundance of light; an instinct for rythmic relationships that arches over wide spaces of forms—length, the need for a rhythm with wide arches, is almost the measure of the force of inspiration, a kind of compensation for its pressure and tension.

“Everything happens involuntarily in the highest degree, but as in a gale of a feeling of freedom, of absoluteness, of power, of divinity—the involuntariness of image or metaphor is strongest of all, one no longer has any notion what is an image or a metaphor : everything offers itself as the nearest, most obvious, simplest expression.”69

I do not quote Nietzsche here in order to laugh at him so much as with him, for he, too, has greatly simplified things, it seems, virtually explaining the artist’s activity in terms of a tension between opposites, even after warning us against it.—”Everything happens involuntarily in the highest degree, but as in a gale of a feeling of freedom….” How such a “free spirit” can be so struck with “amor fati” is indeed puzzling. Given his own forewarning, however, we can hardly be surprised upon discovering a hidden complexity in this simple account. For between the artist and the things themselves a great and teeming depth opens up, “a depth…in which even what is most gloomy and painful does not seem something opposite but rather conditioned, provoked, a necessary color in such a superabundance of light….”

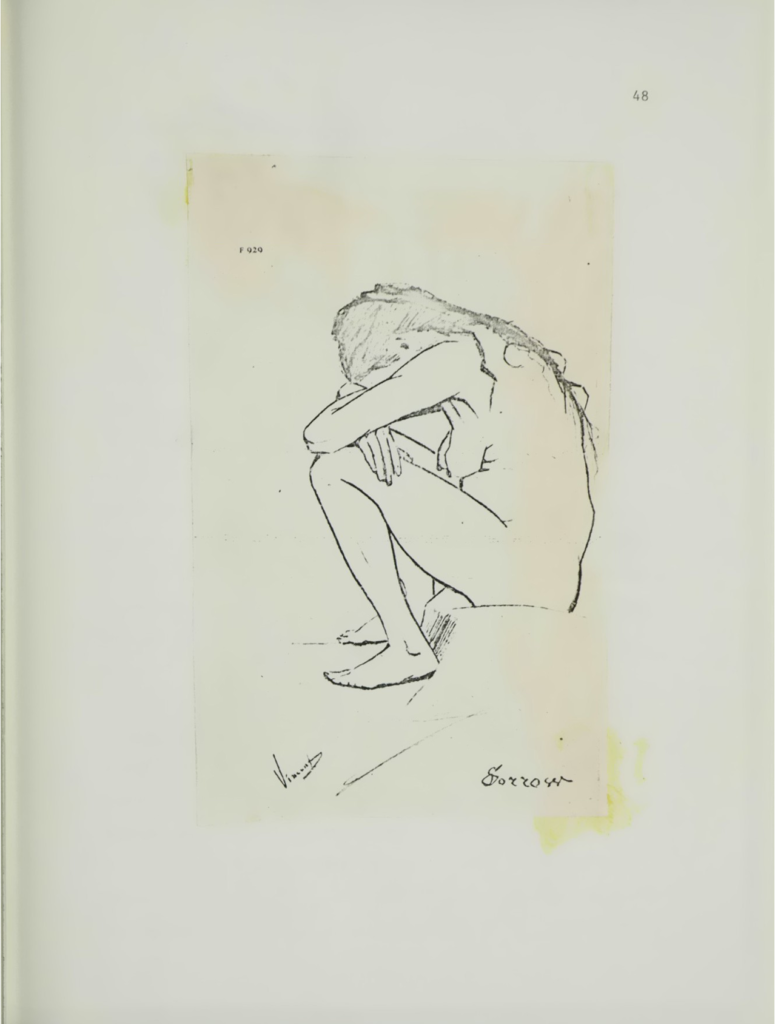

If Shapiro has overlooked something about the depth of Vincent’s perspective, it is just that depth to which Nietzsche is pointing here. When Vincent says, concerning the Wheatfield with Crows, that he had no trouble expressing “sadness and extreme solitude,” and then turns right around to add that we will also see there what he finds so “healthful and strengthening in the country” he did not mean to say that he had rid himself of his ‘sadness and solitude,’ but, on the contrary that he had once again expressed it. Indeed, one need only look at one of his earliest wood cuts of a foresaken, and sagging pregnant woman in the nude with the word Sorrow scratched in large letters across the bottom to know that grief and sorrow were a continuing theme for this artist throughout his career.

It is the depth of Vincent’s painting in this respect, that allows for such ’contradictory remarks,’ it seems. There is as much room for sadness and sorrow in the Wheatfield with Crows as there is room for that dark and sunless sky—in the end, it only serves to accentuate all the more the healthful and strengthening glow of the earth’s own shining radiance.

From the painter, to the painting, to the things themselves— every which way we turn, it seems, contradictions emerge to plague our understanding, as though language, itself, was always playing tricks on us the very moment we try to express what seems to strike us so clearly in the first place. But the inspired man doesn’t let this hold him back:

“It is in life as in drawing: one must sometimes act quickly and decidedly, attack a thing with energy, trace the outlines as quickly as lightning. This is not the moment for hesitation or doubt;…and one must be so absorbed in it that in a short time something is brought onto the paper that was not there before, so that afterwards one hardly knows how it has been hammered off,” Vincent once wrote.70

Imagine standing face to face with another man on the street, for example. You don’t—simply at the sight of another man’s face as he glances over your shoulder behind you—suddenly wheel, dodge, draw your gun, and fire, not at the man who just sneaked up behind you, but at the one behind him and off to the left, by ‘thinking’ your way through the ‘act.’

Skilled or unskilled our actions are not the result of intellectual commandments so much as they are perceptive responses. We are attuned, not simply to what directly confronts us, but through what confronts us, we keep in tune to our whole surroundings. Although we don’t know how, certain bodies seem to have at least a ‘fair idea’ of the significance, not only of what is seen immediately ‘up front,’ but also how much that has to do with what is going on ‘behind one’s back.’

If I too might be excused for indulging in the ‘science of simplification,’ we could call this ‘seeing of significance in a glance’ the ’effective-union’ of subject and object, or any other number of ’contradictions’ implying this dichotomy, which, once lived through, might better be called paradoxes because, when done well, it affords a sense of gratification, not so much in the marvelous nature of one’s own action, or even at the marvelous coincidence of that bullet with its target, but at the even more marvelous appearance of the ‘effective-union’ of what one is doing ’over here’ and what it is that’s happening ’over there.’

If we ’think’ about it, perception falls easily into a dichotomous confrontation of subject and object. But if we can bring ourselves, or somehow be brought to think twice about this confrontation we begin to realize how enigmatic these terms ’subject’ and ’object’ really are. And if the terms of our understanding of perception are enigmatic, how much more enigmatic is that bewildering perception, itself, which gives rise to our ’concepts’ in the first place. As Vincent, himself, once put it: “If life in the abstract is an enigma, in reality it is already an enigma within an enigma.”71

The point is not for a philosopher to rid life, or art, of its enigmatic and ambiguous character; but to sound the depths of each enigma and through the ambiguities to approach a fuller appreciation of their meaning.

Let us sound out one more enigma concerning the ’activity of the artist,’ for example. If everything appears to be not just ’approaching us,’ or ’addressing us,’ but ’rushing towards us’ in some “ominous” fashion in the Wheatfield with Crows, this may simply be due to the gusty winds of an approaching storm. In fact, much of what we take to be the “vehemence,” even “furiousness” of Vincent’s “emotional brushwork” may actually be the work of the wind itself. Vincent devised an arrangement of wire and metal stakes to secure his easel in strong winds, and he himself remarks that while he could tie his canvas down his brush stroke was nonetheless affected. This is not to say that there was nothing slap-dash about Vincent’s own execution of the gesture, but how much the apparent ’’vehemence” of his work is actually the vehemence of the wind is, nonetheless, a legitimate question.

Everything so far suggests, however, that precisely here we don’t have to ’choose.’ The sky is certainly dark and tumultuous looking, and there certainly is a flock of crows coming towards us as if gliding on the gusty winds preceding a storm. And here is Vincent, his “reason half-foundering,” another “person out of work,” feeling sad, lonely, and abandoned. The work which he and his brother have scratched out is now threatened with imminent collapse, his whole society, it seems, is decadent and bordering on collapse; and yet, for one more day, his work sustains him—not by overcoming that sadness and solitude through some cathartic purge, but through expression making it bearable.

Or was it that summer thunderstorm and the unexpected arrival of those crows which suddenly embodied for Vincent his own extremity of feeling—thus allowing him to paint it with such “ominous” precision? This ’inspired’ painting has finally come to look less like the work of a lone artist than like a conspiracy between man and nature in which Vincent, the wind, and the crows all played a hand.

Without pretending to exhaust the meaning of this painting and at the same time standing to benefit from all we’ve been through, let us cast a parting glance at the Wheatfield with Crows. Having,for some time now, been put on the spot with respect to this painting, I invite you to join me, for a spell, on a little rise in the wheat-fields, at the crossroads of sense and non-sense. Storms are threatening from without and within, it’s true. But for the moment, look, at the way that wheat rolls in waves like a glittering, golden sea, feel the wind on your face, smell the freshness of the open air, and, if you can, catch the startling and profound arrival of those crows, who came, perhaps, not simply to tell you something, but also to see what you, yourself, might have to show. And if, somehow, you succeed in catching those crows on the wing, who knows, perhaps they will come to stand, along with everything else in sight, in a glowing, radiant, and very earthy light.

FOOTNOTES

- Titled Champ de ble aux Corbeaux in the French it has been variously translated into English as Cornfield with Crows, Crows in the Wheatfield, even Cornfield with Rooks. My friend Donnie suggests that it is actually a field of barley. Throughout this paper it will be called Wheatfield with Crows.

- Poetry, Language, Thought, “The Origin of the Work of Art,” by M. Heidegger, translated by A. Hofstadter; Harper & Row, Pub. 1971; pg. 17.

- The Complete Letters of Vincent van Gogh, New York Graphic Society; Greenwich, Conn., 1959; Vol. I, pg. 447.

- Letters, op. cit. 3 ; Vol. III, pg. 478.

- Ibid., Vol. II, pg. 185.

- Ibid., Vol. I, pg. 269.

- Ibid., Vol. III, pg. 298.

- Ibid., Vol. III, pg. 459.

- The World of Van Gogh, R. Wallace; Time-Life Books, 1969; pg. 51.